SHAPED MONOCHROMES

SERGIO CAVALLERIN BETWEEN POP ART AND CONCEPTUALISM

by Giorgio Bonomi

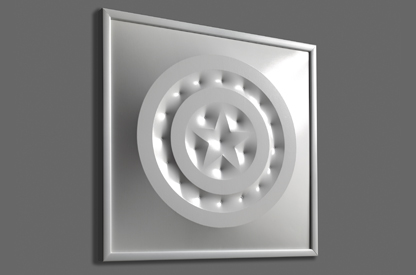

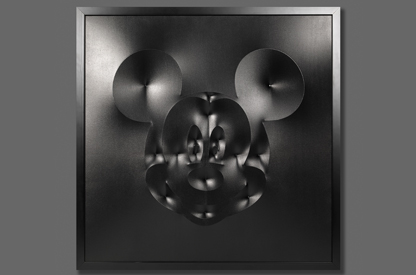

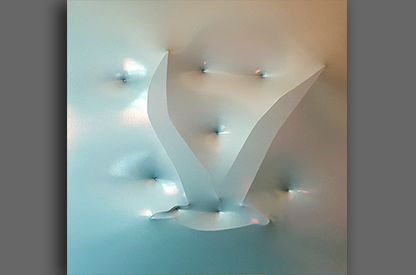

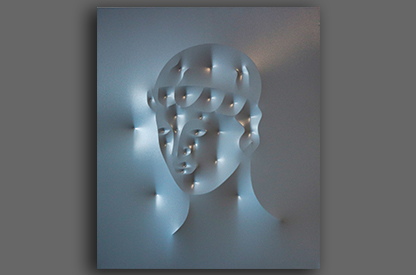

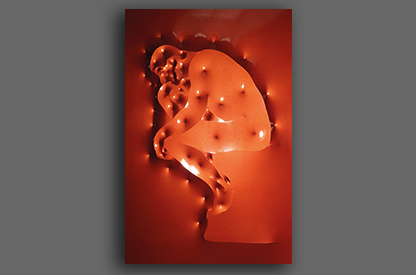

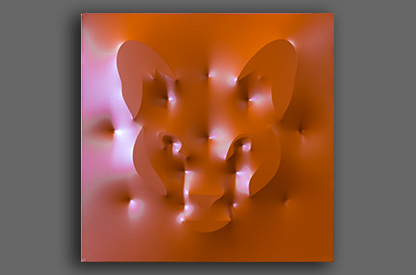

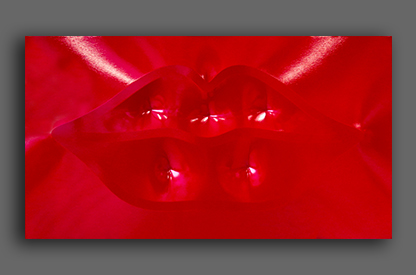

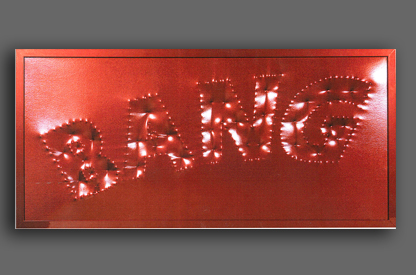

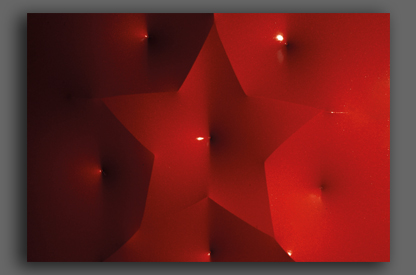

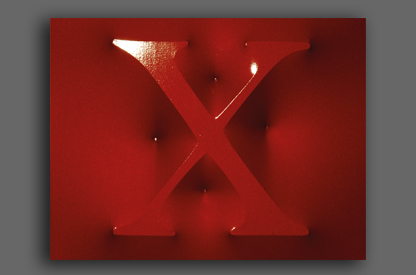

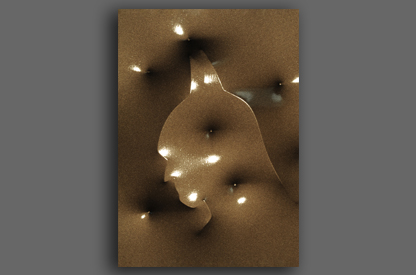

Like many artists, Cavallerin works in “cycles” or “themes”: along with his “disseminations” of images (the Polymers), we have the icons influenced by comics1 the “fantastic” icons, as well as the illustrations for children and adults, or more traditional images. Make no mistake, this is no random eclecticism; in fact, Cavallerin works with rigour and with certain mainstays: the manual skill in drawing and executing the artwork, the experimentation, the ubiquitous humour of his subjects, the conceptualism that makes of him a contemporary artist and prevents all misunderstanding; a conceptualism based on the unity of opposites. These “opposites” (war/peace, hate/love, full/void, movement/stasis, etc.), believed to be the foundation of reality already by Heraclitus, in ancient Greece – since one element cannot exist without the other, a concept reiterated by Hegelian dialectics – the opposites, that is, that the Artist depicts as reality and play, figurative and abstract, originality and trivial image, and so on and so forth. What is more, there is one aspect of this artist’s poetics that must be underlined: the fact that his connection to the history of modern art is without artifice or deception. On the contrary, his sources are obvious, intentionally bared for all to see. In certain series of works, his iconography is clearly influenced by cartoons, while the polymers and other works display an affinity with Pop Art. This is Cavallerin’s way of acknowledging that the history of art is like a “great chain”2, which connects each artist to one or more artists who came before. In other words, all artists have mothers and fathers, yet despite having similar DNA, each one develops their own personalities. After this brief introduction, let us look at the more recent series of works presented here. These “superficidinamiche” [dynamic surfaces], although in many ways an evolution of previous series, which they do not disown, undeniably diverge. Let us get right into examining the most obvious features of these works. The first is “the shaped canvas”: that is, the surface of the painting is not flat – it protrudes and sinks, with convex and concave parts. In contemporary art, shaped canvas first appeared in a work by Alberto Burri (Gobbo [Hunchback], 1950) where, behind the canvas, the Umbrian artist placed a branch to push the surface outwards; Burri later created other “Hunchbacks” with iron rods behind the frame. A few years later, Enrico Castellani and Agostino Bonalumi, among others, made shaped canvas the trademark of their poetics: the former’s works are more minimalist, geometric, linear, “colder” – while the latter’s art is “warmer”, almost baroque in its curved lines and bulges. The other common feature in the work of these two artists is their nearly absolute monochrome3. In Cavallerin, concavity and convexity are essential to the “design” of the work: in fact, he uses this technique to give “body”, light and shadow, relief and movement to the figure; what is more, the absolute monochrome renders the image “surreal”, “metaphysical”. It is not coincidental that all these works, aside from their specific titles, are all part of a series which is aptly named superficidinamiche [dynamic surfaces]. In fact, the canvas has its own rhythm – it undulates, vibrates, moves, even “flicks” – hence it is “dynamic”. The majority of icons in this series come from the world of comics: from Mickey Mouse to Batman and Spider-Man. At the same time – and this is where the influence of Pop Art is most pronounced – we have other works that depict a word, like Bang, or the Nike logo (Sportswear). There’s even a homage to Made in Italy, depicted by the country’s geographical shape. A sense of humour is obvious in all the works, in the titles as well as in the images. Do remember, however, that parody is a powerful vehicle for conceptuality and “seriousness”, it is not merely a game or “mockery”. We have seen similar iconic images in the work of other Italian artists, such as Luciano Fabro or Maurizio Cattelan. In the polymers – the “Dov’è...” [Where is...] series – the twist is, so to speak, more “complicated” or, rather, more “complex” (consisting of several elements). Here we have a multitude of diminutive subjects, all equal and numerous, repeated on the surface, among which another figure appears – or, better, “must be found” – that gives meaning to the whole work: for example, an Italian flag is hidden among a myriad others from around the world; a small hammer appears among a number of small sickles. The works are completed by the titles, that carry their deeper significance: Dov’è l’Italia [Where is Italy], Dov’è il martello [Where is the hammer]. In this more recent series, the image is neater, perhaps more “commanding”, sometimes even “sumptuous”, without however losing any of the humour and sense of “displacement” that is always engendered by art. Monochromy, which was shown by Malevič to be hiding great strength behind its apparent simplicity, gives the painting a “strong”, perhaps even ”virile” tone. We should also point out that the works stand out by the sheer technical, manual skill shown by Cavallerin. If we look at the back of the frame, we see it is a complex construction, made with pieces of wood that make the convexity and concavity possible. At the same time, the canvas is painted with a technique that gives it a “glossy”, “plastic” (in the sense of plastic material) finish, although the very shapes create a “plastic” (in the sense of “sculpted”) effect. It would seem that Cavallerin, in the prime of his life, has also reached artistic maturity – the one that all artists seek and which, fortunately, most only “approach”, since reaching “perfection” would silence their artistic voice. In fact, as we have implied above, the compositions now are “calmer”, more “self-assured”, without the need for “variety in repetition”, but rather pours all its determination, sense of humour, consistency with the history of art (personal and universal) in an atmosphere above worldly preoccupations but with an aura of uneasiness, given that worldly things are always “ambiguous” (in the conceptual sense) and never carved in stone once and for all.

1 Remember that Sergio Cavallerin is also one of the leading personalities in the Italian and international comics publishing industry.

2 This concept can also be found, in a different context, in the title of a famous philosophy book, The Great Chain of Being by Arthur O. Lovejoy, Harvard University Press, 1971.

3 See also our Oltre la superficie. Attraversamento, estroflessione, disseminazione, catalogue of the exhibition of the same name, Perugia, CERP, 14 July-2 September 2011, Benucci Editore.

ART AT THE PALACE

by Azzurra Immediato

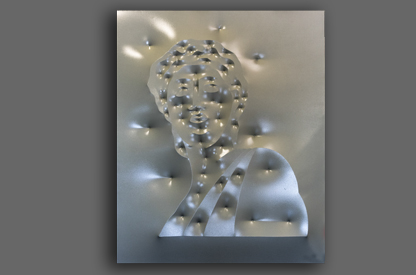

[At a time when] the individual stands alone, surrounded by an unreal reality – sped up, slowed down, repeated, brought forward and put off – with no true point of contact. The words of Agostino Bonalumi – part of a longer text which is thought to be the last conceptual essay by the late artist, who passed away in 2013 – show the extent to which he lamented the momentous dearth of experience for the artist, who no longer claimed the principle his research had been based on, i.e. objectuality of art as experience, of a painting/object as expression of a new identity entrusted to the canvas, a space to be construed as a place renewed by other borders, in tune with the experiments and research of Enrico Castellani. This is the trajectory seemingly followed by artist Sergio Cavallerin, who makes his long-awaited return to Bologna for the collective exhibition Arte a Palazzo - From Bologna to London at Galleria Farini, with a shaped canvas that bears the title “Dynamicemera”, created in 2017. This piece is nothing like the one that the reader may remember from last spring’s exhibition, a painting with a Pop leaning. For the 23rd International Collective organised by Galleria Farini Concept, Cavallerin presents something different: a piece executed with a highly expressive technique, whose powerful syntax affects the phenomenological construct as well as the relationship formed with real space, a relationship of ever-shifting subordination. Dynamicemera is a transfiguration of a classical icon, yet straining to escape the canvas, to invade the surrounding space, in an utterly physical and, at times, unsettling manner – aided by the colour silver, chosen for its shimmering monochrome. Cavallerin’s chosen deformation is, in fact, moulding matter, giving shape to a humanised, anthropomorphic geometry that successfully attempts to transcend the mere representative plane, according to values that translate into rigorous, methodological advance in the known space of the canvas. Dynamicemera is the evolution of a language that is deeply rooted in classical figurative sculpture and painting; as is always the case when there are close ties with intellectual satire, Sergio Cavallerin, once more, breaks free of all convention. Bonalumi also said: “The more a work of art manages to be an accumulation of doubt, while trying to rearrange itself into orderly research, the more important it will be.” An ontological riddle that, in the case of Cavallerin, still follows that subtle, playful line that looks under the accumulated dust of tradition to find new, altered conceptual surfaces – a means for starting a dialogue with the observer in the context of an investigation with multiple solutions, exactly like the canvas which, in this case, becomes utterly dynamic. The typical alphabet of shaped canvas plays the part of a kinetic optical illusion, where perception does battle with the play of light and shadow, ebbs and flows of the surface. Nothing is left to chance, however; as it becomes obvious from the final figure of Dynamicemera, a complex weave and weft of chiaroscuro and geometrical shapes underlies this dynamic, based on a painstaking study of a prominent design which is revealed, on second viewing, to be essential and not a mere exercise in style. Once more, Sergio Cavallerin works according to Maieutics, mixing and melding a profoundly subjective view with an undeniable objectuality that defies interpretation beyond what is visible, the tangible sign of a reality, albeit one that has been transformed.

About Superficidinamiche

by Giulia Naspi

Take pop culture, with all its arresting images, its symbols, and its brands (in the parlance of today), each one the offspring of a very precise time in the capitalist, consumerist era that we still live in, and mix it with the spatial experiments of Italian art of the 1960s. What you get (and much more) are Sergio Cavallerin’s Superficidinamiche. In the concave and convex surfaces we recognise very familiar symbols that are part of our modern culture, of our everyday life – both physical and virtual: the Nike logo, Facebook’s “F”, Mickey Mouse, Darth Vader, as well as Rodin’s Thinker, a statue that has been elevated to the status of an icon. This is the iconography of our times, figures that, since the 1960s, have overwhelmingly joined the more traditional subjects of contemporary art, and which Sergio Cavallerin combines with a new way of conceiving space in art, the roots of which hark back to Fontana’s Spatialism up to the triumph of shaped canvas, the works of Enrico Castellani and Agostino Bonalumi. Everything revolves around that sixth decade of the past century, when these two artists, very close to Piero Manzoni, started exploring new frontiers of the pictorial space, by cutting, painting, stretching canvases, and using the classic materials of traditional painting in a way that had little to do with Picasso’s earlier research into rendering three-dimensionality or with Italian Spatialism. The space created by a shaped canvas is no longer bounded by the frame. The frame is still there but it acts as a window, which the subject leans out of and becomes a space in itself. It does not encroach on us, but accompanies us like the chit-chat between neighbours over the balconies. The colour, the canvas, the nails become places, tactile, hence real objects, halfway between painting and sculpture, where even the strict monochrome becomes sculptural and two dimensions become three. Sergio Cavallerin, however, does not call them shaped canvases; his surfaces are “dynamic” because, if the jutting surfaces of a Bonalumi flex towards the viewer, the artist from Perugia focuses his research on the sophisticated system hidden under every nailed and expertly painted concavity. Thanks to his skilled craft, Sergio creates actual living organisms that try to interact with us, to live in and become part of our space, and that owe their dynamism and “life” to the light that caresses their rippled surfaces, thanks to which the shiny monochromes transmogrify and almost turn the painted matter into industrial materials, such as molten plastic, steel and metal. Cavallerin’s Superficidinamiche are one of the most accomplished experiments in the creation of the space-time dimension that is grounded in the research of the post-war period, elevating it to a level that exceeds all previous achievements and is a reflection on the importance of manual skill in the age of virtual reality.